In my clinical experience, I’ve seen many cases of thyroid problems go undiagnosed (or misdiagnosed) because most doctors don’t perform a comprehensive test panel.

I spent almost a decade undiagnosed because I only had one marker tested. My thyroid condition was missed completely, leading me to deal with needless “mystery” symptoms like chronic fatigue, depression, anxiety, and many others, for far too long!

I still have a copy of my lab results from 2008, before I was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s. At that time, I was desperately searching for a reason behind my exhaustion, hair loss, anxiety, and digestive issues. According to this lab report, my TSH was at 4.5 μIU/mL, yet there was a note written from the doctor declaring: “Your thyroid function is normal, no need to do anything.” Perhaps a TSH of 4.5 μIU/mL would have been normal for a 95-year-old woman, but I was 25 and sleeping 12+ hours a night to feel rested!

Of course, even as a pharmacist, I didn’t think to question the doctor — and most people don’t.

If you suspect that you may have a thyroid condition, or know someone who does, this article will go over all of the most helpful tests that can help you identify a thyroid condition.

This article will also teach you how to understand your labs so that you can advocate for proper treatment for yourself.

In this article, I’ll go over:

- The top thyroid tests that I recommend

- How to interpret your results

- Understanding reference ranges

- How often you should test your thyroid

- How to use lab results for medication adjustments

Thyroid Tests 101

Testing thyroid hormone levels is the first step in diagnosing a thyroid disorder and determining the appropriate course of treatment. However, I’ve found that many doctors don’t test for Hashimoto’s, despite having their patients present with symptoms of thyroid disease.

Due to conventional guidelines, most primary care doctors simply test one’s TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) and T4 levels (the amount of the T4 thyroid hormone circulating in your blood), to screen for hypothyroidism. However, these tests are not always interpreted correctly, don’t differentiate between non-autoimmune thyroid issues and Hashimoto’s, and often miss the subtle fluctuations of thyroid hormones and elevated thyroid antibodies that occur in the early stages of Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism. These stages are often symptomatic and may last a decade before the TSH or T4 levels are flagged as abnormal. Sadly, from personal experience, conversations with other functional practitioners, and hearing reports from clients, I’ve often seen that people with these early stages of Hashimoto’s are told “Your thyroid tests are normal, there’s nothing wrong with you”, even when they are clearly exhibiting symptoms of thyroid dysfunction that could be clearly confirmed by additional testing.

For this reason, it’s important to have a full thyroid panel done, which includes not only TSH and T4, but also T3, and the two most common Hashimoto’s antibodies, TPO and TG antibodies (when they are elevated, they indicate an autoimmune process within the thyroid gland, and their level can indicate the strength of the autoimmune attack against the thyroid gland and can help with predicting a timeline of full thyroid destruction).

Additionally, an ultrasound test can help to diagnose Hashimoto’s, as well as reveal what’s happening with your thyroid and see if there are any nodules present.

I’ll go into detail about why each thyroid test is important below, but I do recommend getting a full thyroid panel done so that you have all of the information necessary to take charge of your health. (1)

Please be sure to review the bottom section of this article about lifestyle, medications, and supplements, as there are several other factors which may affect your thyroid test results.

Please note: The recommendations in this article are based on my clinical experience, and follow current research and recommendations by practitioners in functional medicine. They may not be recognized by doctors who are not familiar with functional medicine.

How to Order Your Lab Tests

If your doctor is ordering thyroid labs for you, be sure to request a copy so that you can see them for yourself and ensure that they are interpreted correctly.

Additionally, I have included self-order options for most of the labs discussed, in case your current doctor won’t order the labs for you.

The self-order options are discounted panels that I set up with Ulta Labs and can be ordered almost anywhere in the U.S. (direct access testing is prohibited by law in New York, New Jersey, and Rhode Island). You will receive a lab order that can be taken to your local lab, and the results will be sent to you electronically.

You can order each individual test that I recommend below, or you can order the entire discounted panel (TSH, free T3, free T4, TPO antibodies, TG antibodies) here.

In many cases, you can self-order the labs and then send the receipts for reimbursement to your insurance. (Please check with your insurance FIRST to ensure that they will accept this and what their procedure is.)

Now, let’s take a look at each thyroid test and what they mean for your thyroid health.

1. The Thyroid Screening Test

The thyroid stimulating hormone, or TSH test, is used as a screening test for thyroid disease, as well as a test for monitoring the correct dose of medication needed for an individual.

This is an important test that I recommend getting every time you check your thyroid function.

TSH is a pituitary hormone that responds to low/high amounts of circulating thyroid hormone. If you’re new to thyroid lab testing, it may seem counterintuitive, but an elevated TSH means that you do not have enough thyroid hormone on board and that you are hypothyroid. This is because the TSH hormone senses low thyroid levels and is released when there is a lack of it, in an effort to signal the body to make more.

In advanced cases of Hashimoto’s and primary hypothyroidism, this lab test will be elevated. In the case of Graves’ disease and hyperthyroidism, TSH levels will be low. People with Hashimoto’s and mild or central hypothyroidism may have a “normal” reading on this test.

If you’ve been a thyroid patient for a while, you’re probably thinking to yourself, “Well, of course, doesn’t everyone know that?” — and I have to warn you… I’ve unfortunately seen physicians who have mistakenly thought that a low TSH meant one had an underactive thyroid, and a high TSH, an overactive thyroid — putting their patients in really dangerous situations by under- or overmedicating them!

In recent years, The National Academy of Clinical Biochemists indicated that 95 percent of individuals without thyroid disease have TSH concentrations below 2.5 μIU/mL, and a new normal reference range was defined by the American College of Clinical Endocrinologists to be between 0.3 and 3.0 μIU/mL. (2)

However, in my experience of reviewing the labs of thyroid patients from around the world, many labs have not adjusted that range in the reports they provide to physicians, and some even have ranges as lax as 0.2 to 8.0 μIU/mL. Thus, conventional medicine practitioners will likely follow the standard reference range for TSH to determine if a person has hypothyroidism — in some cases, they may even follow a more lax range if the lab they are using hasn’t updated their levels, or if the practitioner is not familiar with newer guidelines.

In any case, physicians who follow “standard” reference ranges may end up telling their patients that their thyroid is normal, when in fact, they have a thyroid condition! And many physicians may miss the patients who are showing an elevated TSH. This is one reason why patients should always ask their physicians for a copy of any lab results.

Some practitioners consider a range of between 0.35 mIU/mL and 4.50 mIU/mL as normal, while others suggest using a range of between 0.5 mIU/mL and 2.50 mIU/mL as normal. (3, 4) However, many of my colleagues in the functional medicine community, as well as myself, have further defined that normal reference ranges should be between 1 and 2 μIU/mL for a healthy adult not taking thyroid medications. And thus, for optimal health, a person with hypothyroidism should be properly treated until their TSH reflects that of a healthy person with optimal function. 🙂

When I was in Poland to find distributors for the Polish version of my first book back in 2014, I happened to visit one of my relatives who was wearing a heavy winter coat on a warm spring day. In speaking with her, I was able to tell that she was experiencing a great number of thyroid symptoms, and she confided that her doctor had said her thyroid was normal. I looked at her labs, and sure enough, her TSH was around 5 μIU/mL, and she was never tested for antibodies nor offered a thyroid ultrasound. (I often share that at the time of my diagnosis, I was living in Southern California and sleeping under two blankets, and was walking around with a TSH of 4.5 μIU/mL – and guess what, I survived living in Colorado for six years when my thyroid was optimized. :-))

I have found that I, as well as many other thyroid patients, feel best when my TSH is between 0.5 and 2 μIU/mL (for elderly clients, up to 2.5 μIU/mL). Some integrative professionals will go as far as to say that people should have a TSH of right around 1 μIU/mL or below 1 μIU/mL, to feel their best.

That said, the TSH test is not the only test that should be used to diagnose Hashimoto’s since, in the early stages, one’s TSH level may fluctuate or remain within the normal limits.

Most conventional practitioners will stop further thyroid testing when they determine the TSH is “normal” (that is, within the outdated, old school “normal” reference range).

This is why, even if you’ve been told your thyroid is normal, and even if your TSH is between 0.5 and 2 μIU/mL (the range I recommend), you need to test your free T4, free T3, and especially thyroid antibodies (TPO antibodies and TG antibodies), to truly determine if you have a thyroid condition.

Recommended test: TSH

Optimal reference range: Between 0.5 and 2 μIU/mL

How often you should test: Every four to six weeks when starting a new medication, then every six months if symptoms are stable.

Things to consider before testing: I recommend testing your TSH early in the morning, and delaying your thyroid hormones until after taking the test, to ensure accurate results, especially if you are taking T3-containing medications. Taking your medications before the test can suppress your TSH and make it look like you are overmedicated when you are not. Additionally, the supplement biotin, commonly used for hair loss, can also suppress TSH levels, making it look like you are overmedicated, or like you are hyperthyroid. The American Thyroid Association recommends that patients stop taking biotin for at least two days before a TSH test.

2. Thyroid Hormone Level Tests

There are four main thyroid hormones that have been identified: T1, T2, T3, and T4.

T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine) are the two main thyroid hormones. T4 is known as prohormone and is 300 percent less biologically active than T3. T3 is the main biologically active thyroid hormone and gives us beautiful hair, replenishes our energy, and runs our metabolism. (5)

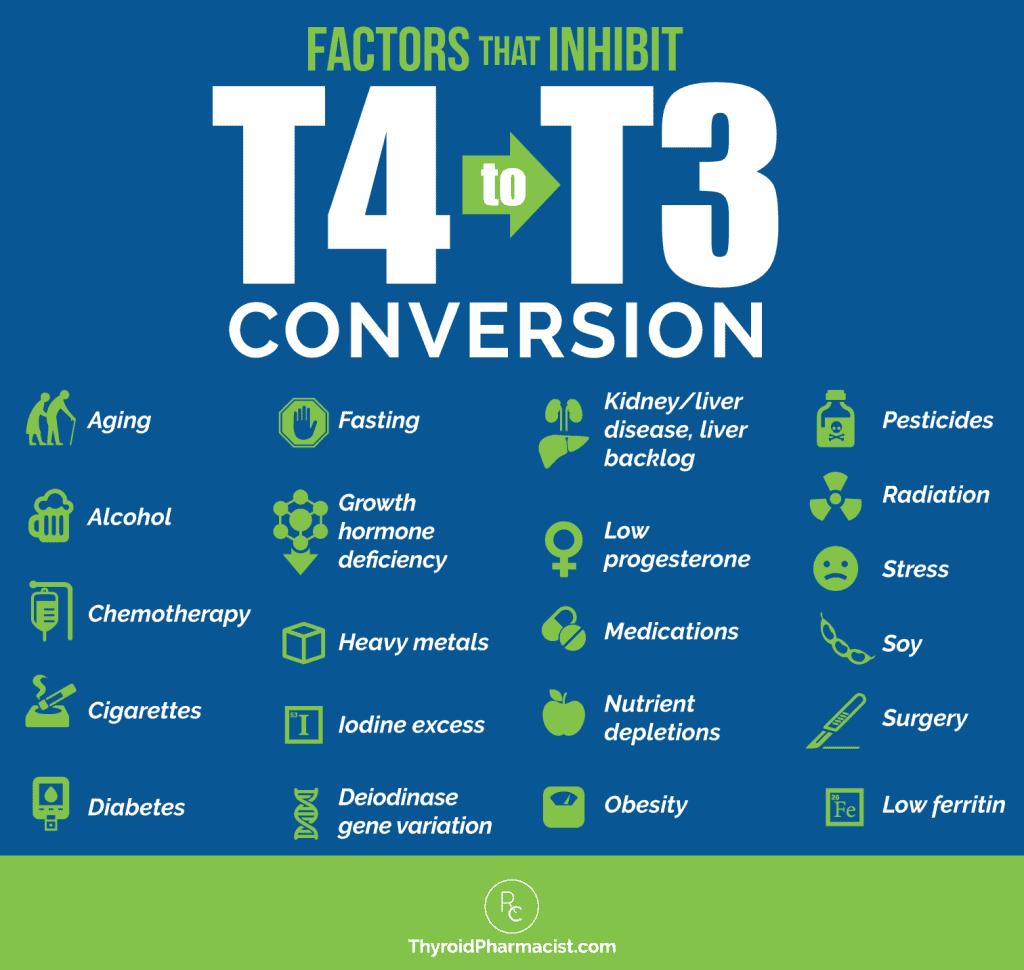

You may have put together that most of the commonly prescribed thyroid medications like Synthroid and levothyroxine, only contain T4 (thyroxine), and thus they need to be converted to the active T3 form in the body.

On paper, the T4 to T3 conversion happens just fine, but in the real world, in real human bodies, we may not always convert T4 to T3.

We can reveal our T4 to T3 ratios and measure the hormone that is available to do its job in the body, by testing our free T4 and free T3 levels.

Free T3 and Free T4 tests measure the levels of active thyroid hormone circulating in the body. (When these levels are low, but your TSH is in the normal range, this may lead your physician to suspect a rare type of hypothyroidism known as central hypothyroidism. I’m working on an article on this topic, so stay tuned!)

Some clinicians may only test for T4, but T3 is also important to test, as some individuals may not be converting T4 to the active T3 properly. Thus, people may have a normal T4, but a low T3 level.

How Do You Know If You Are Converting Correctly?

Take a look at your free T3 and free T4 levels. Both should be in the optimal ranges noted below, which have been determined by functional medicine guidelines and my clinical experience. If the T4 is optimal, but the T3 is below the optimal range, you know that your body is not making enough T3 hormone from the T4.

Recommended test: Free T3 and Free T4

Optimal Free T4 reference range: 15 to 23 pmol/L

Optimal Free T3 reference range: 5 to 7 pmol/L

How often you should test: I recommend testing every four to six weeks when starting a new medication, every two to three months if tracking the impact of lifestyle changes, and then every six to 12 months once symptoms are stable.

Things to consider before testing: I recommend testing your free T3 and free T4 early in the morning, and delaying your thyroid hormones until after taking the test to ensure accurate results, especially if you are taking T3-containing medications. Taking your medications before the test can result in a falsely elevated T3 (and sometimes T4), making it look like you are overmedicated when you are not. Additionally, the supplement biotin, commonly used for hair loss, can also falsely increase both T4 and T3 levels, making it look like you are overmedicated, or like you are hyperthyroid. The American Thyroid Association recommends patients stop taking biotin at least two days before a T4 and T3 test.

3. Thyroid Antibodies

There are various types of antibodies against the thyroid gland that can be detected in thyroid disease. The presence of thyroid antibodies indicates that the thyroid gland has been recognized as a foreign invader by the immune system and that the thyroid gland is under attack.

In Hashimoto’s, triggers contribute to the body developing something called “a lack of self-tolerance.” This is when the body is no longer able to recognize its own tissue as part of itself, but instead starts viewing its tissue as a foreign invader. It is no longer “tolerant” of itself, and this is what leads to an autoimmune condition. When the body begins this breakdown of its immune tolerance, we’re initially going to see the presence of elevated thyroid antibodies.

In Hashimoto’s, about 80 to 95 percent of patients have thyroid antibodies. (6) Thyroid antibodies are going to be the first indication of a thyroid problem in many cases. They can be elevated for 5, 10, sometimes even 15 years, before a change in TSH is even detected. Having elevated thyroid antibodies, even in the presence of a “normal” TSH, means that it’s only a matter of time before your thyroid becomes destroyed to the point that it can no longer produce a sufficient amount of hormones.

Some clinicians will say that once you have thyroid antibodies, you will always have thyroid antibodies, so the actual number doesn’t matter, as the antibodies can randomly fluctuate. I respectfully disagree.

I believe that antibodies can fluctuate in response to triggers (some as common as stress), and in my exhaustive experience, they can be an incredibly helpful marker for tracking disease progression.

The most common antibodies in Hashimoto’s are thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO antibodies) and thyroglobulin antibodies (TG antibodies). Most people with Hashimoto’s will have an elevation of one or both of these antibodies. TPO antibodies are the most common and have been reported in 5 to 38 percent of the population, depending on the study! (7-18)

Thyroid antibodies are often elevated for decades before a change in TSH is seen in Hashimoto’s.

People with Graves’ disease and thyroid cancer may also have an elevation in thyroid antibodies, including TPO and TG. However, the most common antibodies found in Graves’ disease are TSH receptor antibodies, including thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) — this marker is elevated in over 90 percent of people with Graves’ disease. TSH receptor binding antibody (TRAb), also known as TSH-binding inhibiting immunoglobulin or TBII, is elevated in over 50 percent of people with Graves’ disease. (19, 20) (You can check for Graves’ related antibodies here.)

Thyroid antibodies can be used for diagnostic purposes and monitored to track remission. As I mentioned, thyroid antibodies indicate an active destruction going on against your thyroid. This destruction often comes with a lot of symptoms that may cause, or be misdiagnosed as depression, panic attacks, anxiety, miscarriage/infertility, carpal tunnel, hair loss, weight gain, fatigue/laziness, and, of course, the most disempowering diagnosis of them all… hypochondria.

Hypochondria is a diagnosis I take great offense to because it ignores the patient’s intuition that there is something wrong. It often leads to shame, disempowerment, helplessness, and the destruction of trust we have in our own mind and body connection, as well as in the healthcare model and of ever getting well.

The good news is that in many cases, when you have elevated antibodies and a normal TSH, you can not only reverse all of your symptoms, but you can also prevent damage to your thyroid gland using a root cause approach.

I found out I had thyroid antibodies in the 2000 IU/mL range, one year before doing a thyroid function retest, when my thyroid function deteriorated to the point where my doctor thought I would benefit from medications. Unfortunately, the doctor that initially ran the antibody test told me not to worry about them, and that there was nothing I could do anyway. I am often saddened that I trusted another person with my health and didn’t do additional research on my own. I was also highly symptomatic at that time, likely due to the elevated TPO antibodies. I had new onset panic attacks, social anxiety, hair loss, digestive issues, and fatigue — common early symptoms of elevated thyroid antibodies.

As a 25-year-old newlywed who had just moved to a new city, I was crippled by my health. Instead of focusing on being a newlywed, making my wedding albums, and meeting new friends, I felt like I was falling apart. The crazy thing is, I am now in my late 30s, with a busy little boy and a business, and I feel 10 times more energetic than I did in my 20s! I no longer grieve the decade I lost to undiagnosed Hashimoto’s, but this is why I’m so passionate about advocating for you to get the proper tests, and for you to understand your tests!

Thyroid antibodies may be elevated for many years before a change in TSH is seen, and finding antibodies early can often prevent damage to the thyroid, as well as help with preventing the need for long-term medications.

As mentioned earlier, thyroid antibodies can also be used as a marker to monitor disease progression and remission. While any elevation of thyroid antibodies can indicate Hashimoto’s (and some may have seronegative Hashimoto’s with thyroid antibodies not elevated at all), I like to monitor thyroid antibodies in clients.

While not all clinicians will agree to the following ranges, based on research and my clinical experience, here are the numbers I keep in mind:

- Thyroid antibodies above 500 IU/mL are considered a very aggressive case of Hashimoto’s

- Antibodies under 100 IU/mL indicate remission, or a less aggressive case

- Antibodies under 35 IU/mL mean you no longer test for Hashimoto’s according to conventional medicine standards

- Antibodies under 2 IU/mL are optimal (scientists believe that there may be some antibodies present as part of a normal repair process)

I recommend a lot of strategies to make the condition less aggressive and to put it into remission, in my article on reducing thyroid antibodies, as well as in my books Hashimoto’s: The Root Cause and Hashimoto’s Protocol. Be sure to check them out to learn how to lower your antibody levels.

Recommended tests: TPO, TG for Hashimoto’s (and TSI, TBII for Graves’)

Optimal TPO reference range: <2 IU/mL

Optimal TG reference range: <2 IU/mL

Optimal TSI reference range: < 0.55 IU/L

Optimal TBII reference range: 16 to 100 percent inhibition of TSH binding

How often you should test: I recommend monitoring thyroid antibodies every 60-90 days to see if the changes you’re making in your lifestyle are helping you. A reduction in these antibodies, especially when accompanied by a reduction in symptoms, is a good indication that your condition is improving and that you are on the right path with your healing interventions.

4. The Thyroid Ultrasound

Some individuals may have thyroid disease but may not have detectable alterations in their blood work. In fact, research suggests that 10 to 50 percent of people with Hashimoto’s may not test positive for antibodies. (21) In these cases, a person might have a less aggressive version of Hashimoto’s known as antibody negative or seronegative Hashimoto’s.

In these cases, a thyroid ultrasound can be used to find physical changes in the thyroid gland that point to Hashimoto’s.

A thyroid ultrasound will help you and your physician determine whether you have changes consistent with Hashimoto’s (such as a rubbery thyroid, shrunken thyroid, enlarged thyroid, or abnormal growths in the thyroid that are present). Some growths may indicate an autoimmune process, others may indicate benign nodules, and others may signal cancerous nodules.

I can’t locate the reference at the moment, but I have learned that some 10 percent of people diagnosed with Hashimoto’s are diagnosed using an ultrasound, and I recommend that everyone with Hashimoto’s or thyroid disease get at least one ultrasound in their lifetime, especially women of childbearing age. If thyroid nodules are found, then I recommend having an annual ultrasound. (Be sure to read my comprehensive article on shrinking thyroid nodules if you happen to have them.)

A thyroid ultrasound is a very simple, non-intrusive test that only takes about 10 minutes. It uses sound waves to image the thyroid. A lubricant jelly is placed on the skin and a small hand-held transducer is passed over the thyroid. The ultrasound will show any change in gland size and texture. Clinicians can find changes in thyroid size (shrunken or enlarged), tissue density and texture (rubbery), as well as nodules (abnormal growths), which are all characteristic changes found with Hashimoto’s. Growths can also be a signal for cancerous nodules. If there is a concern with that, the next step would be to have a nodule biopsy, and you can read more about that in my article on thyroid cancer.

Recommended tests: Thyroid ultrasound ordered by your physician (I am not aware of self-order options at this time)

How often you should test: I recommend at least one ultrasound for every person, especially women of childbearing age.

5. The Reverse T3 Test

The reverse T3 (rT3) test measures how much of the active free T3 hormone is able to bind at thyroid receptors. RT3 is produced in stressful situations and binds to thyroid receptors, but turns them off instead of activating them. (Stress is a common cause of low T4 to T3 conversion. Under stressful situations, T4 gets converted to reverse T3 instead of to T3. Reverse T3 is an inactive molecule related to T3, but without any physiological activity.) (22)

The rT3 test is sometimes used to identify cases of poor T4 to T3 conversion, as well as thyroid symptoms that are due to adrenal stress, instead of thyroid malfunction or autoimmunity.

However, in most cases, this test doesn’t change my other recommendations, so I consider this an optional test. (I prefer the adrenal saliva test to determine the proper treatment for adrenal stress. An adrenal saliva test gives us the advantage of knowing how to address the reason one is producing too much reverse T3.)

The free T4/free T3 test is more useful for me to determine if a person is properly converting thyroid hormones. In cases where a lot of reverse T3 is produced, adding a thyroid medication that contains T3 ensures that the right hormone is getting to the right receptors.

This test will likely not be used by conventional doctors, but many integrative doctors love the reverse T3 test, and it may be a useful test to monitor your improvement. So if you think that this test (or others listed here that are not part of a conventional assessment) might be useful for you, consult with a functional practitioner in your area. (I have a handy database of functional practitioners here on my website — but please note that I do not endorse or make representation as to the qualifications or business practices of any healthcare provider.)

When assessing your rT3 results, it is important to watch for trends of your levels going up. This usually indicates your body is reacting to a stressful situation. Your body produces rT3 to give it a break and to prevent you from becoming hyperthyroid. This is an evolutionary adaptation to slow your metabolism in times of famine (for more information on this, take a look at my Safety Theory). High rT3 due to stress has a snowball effect on hypothyroid symptoms. The adaptation by the body producing rT3 is not useful in our high-demand society when we must work and take care of our children, spouse, parents, etc.

Recommended tests: Reverse T3 (rT3)

Optimal rT3 reference range: Between 11 and 18 ng/dl

How often you should test: Every six months, if recommended by your integrative physician.

6. Your Symptoms

Last but not least, your symptoms should serve as an important thyroid test. Be sure to listen to your body — only you know its subtle messages!

Our symptoms offer vital clues as to what is going on inside our bodies, and these symptoms can shift as our thyroid hormone levels change.

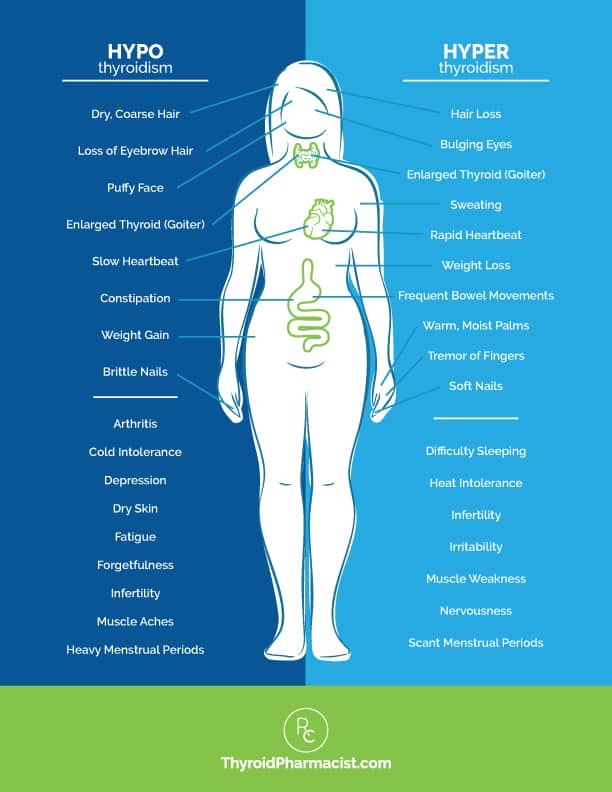

Do you have any symptoms of hypothyroidism, or deficiency of thyroid hormone, such as:

- Slower metabolism leading to weight gain

- Forgetfulness

- Feeling cold or cold intolerance

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Dry skin

- Constipation

- Loss of ambition

- Dry, coarse hair

- Muscle cramps

- Stiffness

- Joint pain

- A loss of the outer third eyebrow

- Heavy menstrual periods

- Infertility

- Muscle aches

- Puffy face

- Slow heartbeat

- Brittle nails

- Arthritis

Or, do you have any symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or an overabundance of thyroid hormone, such as:

- Weight loss

- Palpitations

- Anxiety

- Eye-bulging

- Tremors

- Irritability

- Infrequent menstrual periods

- Fatigue

- Heat intolerance

- Increased appetite

- Hair loss

- Enlarged thyroid gland

- Sweating

- Frequent bowel movements

- Infertility

- Soft nails

- Warm, moist palms

- Finger tremors

- Insomnia

- Muscle weakness

- Nervousness

In addition to many of the symptoms we frequently see associated with hyper- and hypothyroidism, Hashimoto’s commonly presents with:

Some of these symptoms may be directly related to insufficient thyroid hormone. Others may be due to related issues (i.e. gut infections), which I have seen in many people with Hashimoto’s. That’s why it’s important to identify the root causes of YOUR Hashimoto’s, so you can take the first steps toward healing!

Recommended tests: Create a health timeline and use a notebook or chart to keep track of your symptoms.

Reference Range: Score the severity of your symptoms from 1-10, and aim to steadily lower your score by uncovering and addressing your root causes.

How often you should test: I recommend assessing your symptoms on a weekly basis until you feel you have eliminated them.

Interpreting Your Labs

Once you have your labs, what do you do with them? What do they mean?

I frequently get messages from readers asking me to comment on their thyroid labs. Of course, I can’t provide medical advice through the internet without doing a personalized comprehensive case review (this is for your own safety as well as due to professional liability laws), so I wanted to write this little guide for you all to empower you to understand your own labs.

Please note: This evaluation is based on optimal functional medicine ranges and my clinical experience, and may not be recognized by doctors who are not familiar with functional medicine.

Optimal Reference Ranges

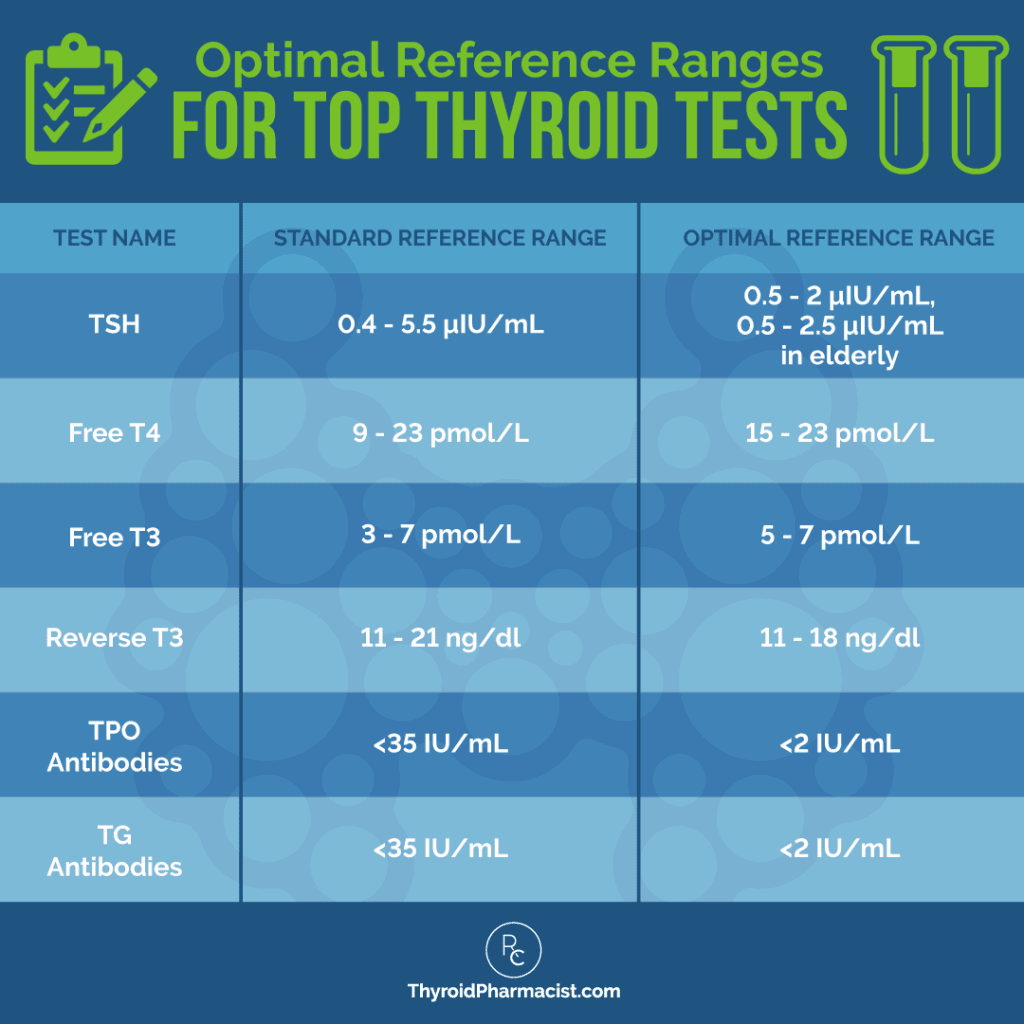

When I look at my client’s labs, I’m focusing on optimal reference ranges. Here’s a handy reference chart I created for Hashimoto’s, based on recommendations from my training with the Institute of Functional Medicine:

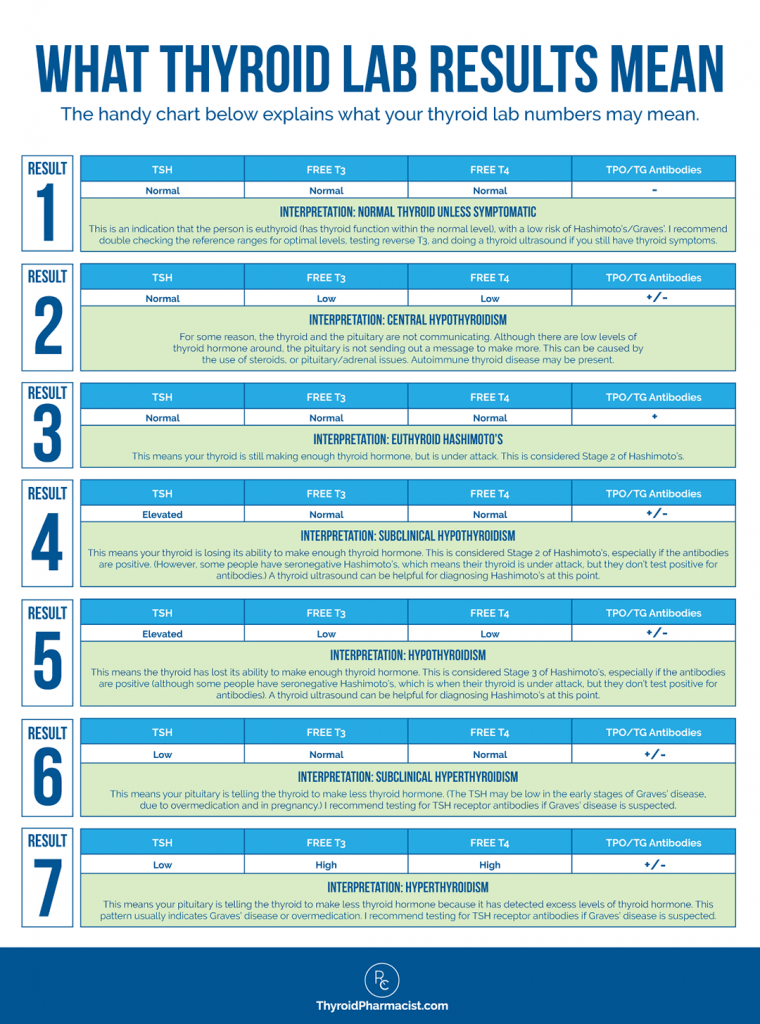

The handy chart below explains what the thyroid lab numbers mean:

Your optimal thyroid numbers are going to be different from your mother’s optimal thyroid numbers, which are going to be different from your neighbor’s optimal thyroid numbers, so it’s important for you to track your thyroid symptoms while tracking your numbers, to determine your “personal best.”

Understanding Thyroid Labs for Medication Prescriptions and Adjustments

Thyroid labs, especially TSH, free T3, and free T4, are critical for determining if you need to start, increase, or reduce the dose of your thyroid hormone medications, as well as if you’re on the right thyroid medications.

Some physicians who prescribe thyroid medications will not prescribe a medication unless the TSH is above 10 μIU/mL, and will be satisfied when a person who is taking thyroid meds has a TSH under 10 μIU/mL. I think this is the reason why many people continue to have fatigue, cold intolerance, difficulty with weight loss, and hair loss — despite taking thyroid medications.

When the TSH is between 2.5 μIU/mL and 10 μIU/mL, and/or when T3 and T4 are within normal limits, this is known as subclinical hypothyroidism. This means that the thyroid is still able to make enough thyroid hormone, but not without sacrifice. At this point, our thyroid is working overtime, leading to many of the common symptoms of hypothyroidism.

The thyroid is constantly getting a signal to make more and more hormone, and your body is likely running out of nutrients (like selenium) to make more hormone. This results in additional inflammation to the thyroid, attracting more antibodies and fueling the autoimmune process. While some may stay in a subclinical state indefinitely, researchers suggest that 2-28 percent of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism progress to overt hypothyroidism, depending on age, gender, and the presence of anti-thyroid antibodies. (23) In my experience, on average, five percent of people with subclinical hypothyroidism may progress to overt hypothyroidism each year due to this and the THEA Score. (Please review my article on thyroid antibodies for more information on this.)

What About Thyroid Medications for Subclinical Hypothyroidism?

Starting thyroid medication in subclinical hypothyroidism is considered controversial by endocrine groups. Exceptions are made for women who are contemplating pregnancy and for those who have overt hypothyroid symptoms. Guidelines clearly state that in order to avoid pregnancy complications and impaired development of offspring, women with subclinical hypothyroidism need to be treated with thyroid hormones. (24)

At this stage, many patients may also opt to “wait and see” and may forgo thyroid medications in an effort to “do it naturally.” I know that I was one of those people, and I waited six months to get on medications after my diagnosis, but knowing what I know now, I am in favor of starting medications for subclinical hypothyroidism.

Why?

Korzeniowska and colleagues at the Medical University of Gdansk found that treating children with subclinical hypothyroidism with thyroid hormones, resulted in a decrease of inflammation. (25) This means that the medications gave their thyroids a rest and resulted in a slowing down of the autoimmune attack, manifested by lower levels of thyroid antibodies.

Additionally, in my clinical experience, most patients with subclinical hypothyroidism report feeling much better when they start on thyroid hormones.

Personally, when I was first diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism, I didn’t want to take medications because I felt like it would be giving up, and that I should figure things out naturally.

At that point, I started weekly acupuncture sessions, eating Brazil nuts, and using all kinds of magic hair potions to try to keep my hair loss at bay (I was still a young butterfly then).

I wanted to believe that these interventions were keeping me from getting worse… until my husband and I took a red-eye flight from Los Angeles to visit friends on the East Coast in the winter. The lack of sleep combined with the cold weather put me in a hypothyroid flare.

I spent the entire weekend shivering, tearful, and anxious, and was very embarrassed about how much I inconvenienced our friends.

After I flew back to California, I spent a few days getting nourishment from the sun and made an appointment to start medications. I felt much better when I did, and thus I’m no longer a proponent of being a martyr for a senseless cause. Part of loving yourself is knowing when you need help.

If I could do it over, I would have, of course, gone gluten, dairy, and soy free for three months as soon as I had found out I had Hashimoto’s AND started medications. If a three-month trial of diet didn’t result in significant improvement, I would have started digging for my root cause.

After all, when my TSH was at 4.5 μIU/mL, I was sleeping for 12+ hours, and at 3 μIU/mL, my hair began to tangle. I didn’t realize how hypothyroid I was until I was appropriately treated. A little change in the dosage of thyroid medication can make a huge difference.

What About Those Already on Thyroid Medications?

If you’re already on thyroid meds, but still have symptoms, it is possible you may need to up your dosage so that your labs fall within the optimal range, to help you feel better.

Please take a look at my article on TSH for a letter that you can take to your physician if he/she is not familiar with the current optimal reference range. As I mentioned earlier, I personally feel best with a TSH a bit under 1 μIU/mL, but you may need some trial and error to find your personal best TSH.

Once you establish a dose of medication that’s working for you — and as long as your symptoms don’t change (look out for anxiety and palpitations as potential signs of an overdose, and fatigue and pain as potential signs of an underdose) — you can test your thyroid hormones every six months.

You may want to read about the different hormone preparations in my article A Pharmacist’s Review of Medications for Hashimoto’s and Hypothyroidism.

Other Considerations for Hormone Testing

There are some other important factors you should know about that can affect your thyroid test results and hormone levels.

Thyroid medications are goldilocks hormones, which means they need to be used in just the right dose — and there are risk factors of being overmedicated.

I recommend testing thyroid hormone levels every six to 12 weeks while using complementary therapies, including root cause medicine, diet, or supplements that may optimize your thyroid function, improve the absorption of thyroid medications, and/or reduce your requirement for thyroid medications (you know, all the stuff I recommend on my website!), as well as when incorporating new lifestyle changes, to ensure your thyroid medication dosage is optimized, or sooner, if you are showing any of the above-mentioned symptoms.

Symptoms of overmedication include, but are not limited to: rapid or irregular heartbeat, nervousness, irritability or mood swings, muscle weakness or tremors, diarrhea, menstrual irregularities, hair loss, weight loss, insomnia, chest pain, and excessive sweating. Do not start, change, increase, decrease or discontinue your medications without consulting with your physician.

Supplements and Medications That May Interfere With / Alter Thyroid Test Results

It’s important to note that there are various medications and supplements that can alter your thyroid test results.

While some supplements can result in false readings of thyroid levels (such as the biotin I listed above), others reflect a true change in thyroid levels — this change may be an improvement or worsening of levels depending on the supplement. I’ve found that aloe vera, cordyceps, vitamin A, and ashwagandha, can all lower TSH, and myo-inositol could lower/normalize TSH in some cases.

Medications like lithium, amiodarone, and high-dose iodine can cause thyroid damage resulting in a greater need for thyroid hormones. (26, 27) Please read this article for more information on medications that can be toxic for your thyroid, and this article about how to get accurate lab tests for more information on supplements and medications that can affect thyroid lab results.

Please be sure to report to your practitioner any and all medications and supplements you are currently taking, as well as any changes in supplement or medication regimes.

As a final note, false alterations of thyroid labs are not to be mistaken with drug-drug interactions, which occur between thyroid hormones and certain medications, and lead to actual changes in thyroid hormone levels. Simply stated, there are medications that interfere with thyroid lab results by actually interfering with thyroid hormone function — this means they cause real alterations in thyroid hormone levels. Some of these alterations are clinically significant and may require a dose adjustment of your thyroid medications when taking the two medications concurrently. I have an article coming soon on this topic. In the meantime, talk to your doctor or pharmacist.

The Takeaway

It can be a little bit overwhelming to figure out where to start with testing, but I hope the information in this article has helped you understand which thyroid tests you need to ask for, and how to interpret and act on the results.

In summary:

- If you suspect that you may have Hashimoto’s or hypothyroidism, I recommend that you get the following tests for diagnostic purposes: TSH/free T3/free T4 and TPO/TG antibodies, thyroid ultrasound

- If you suspect that you may have Graves’ disease or hyperthyroidism, I recommend that you get the following tests for diagnostic purposes: TSH/free T3/free T4, a thyroid ultrasound, TSI and TBII antibodies.

- If you are monitoring your response to thyroid hormones or thyroid-suppressing medications, I recommend checking your TSH, free T3 and free T4 levels every four to six weeks.

- If you are monitoring for remission, I recommend testing TPO antibodies and TG antibodies for Hashimoto’s, or TSH receptor antibodies for Graves’, every 90 days.

I hope you found this article helpful in navigating your thyroid tests. As always, my goal is to empower you to take charge of your own thyroid health and feel your very best!

Was this article helpful? Did you have an “aha” moment? Do you have additional questions for me about labs?

I’d love to give you my 100-page eBook Optimizing Thyroid Medications (a $19.99 value!) for free! This eBook does a deep dive into the various thyroid medication options available, how to take them properly, and how to work with your doctor to get the right medication and the right dose.

P.S. You can also download a free Thyroid Diet Guide, 10 thyroid-friendly recipes, and the Nutrient Depletions and Digestion chapter of my first book, for free. You will also receive occasional updates about new research, resources, giveaways and helpful information.

To stay connected, please join my Facebook and Instagram pages, where you can ask questions and interact with the thyroid community!

References

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013 Jan-Feb;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028. doi:10.4158/EP12280.GL

- NH, Papaleontiou M. Biochemical Testing in Thyroid Disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2017;46(3):631-648. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2017.04.002

- Sheehan MT. Biochemical Testing of the Thyroid: TSH is the Best and, Oftentimes, Only Test Needed – A Review for Primary Care. Clin Med Res. 2016;14(2):83-92. doi:10.3121/cmr.2016.1309

- Wartofsky L, Dickey RA. The evidence for a narrower thyrotropin reference range is compelling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5483-5488. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0455

- Shahid MA, Ashraf MA, Sharma S. Physiology, Thyroid Hormone. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 8, 2022.

- Fröhlich E, Wahl R. Thyroid Autoimmunity: Role of Anti-thyroid Antibodies in Thyroid and Extra-Thyroidal Diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:521. Published 2017 May 9. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00521

- Amouzegar A, Gharibzadeh S, Kazemian E, Mehran L, Tohidi M, Azizi F. The Prevalence, Incidence and Natural Course of Positive Antithyroperoxidase Antibodies in a Population-Based Study: Tehran Thyroid Study. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169283. Published 2017 Jan 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169283

- Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):526-534. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.4.526

- Staii A, Mirocha S, Todorova-Koteva K, Glinberg S, Jaume JC. Hashimoto thyroiditis is more frequent than expected when diagnosed by cytology which uncovers a pre-clinical state. Thyroid Res. 2010;3(1):11. Published 2010 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/1756-6614-3-11

- Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM. Thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies in euthyroid subjects. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:1-15.

- Wiersinga WM. Thyroid autoimmunity. Endocr Dev. 2014;26:139-157. doi:10.1159/000363161

- Baldini M, Colasanti A, Orsatti A, Airaghi L, Mauri MC, Cappellini MD. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: a twenty-year follow-up of the Whickham Survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;43(1):55-68.

- Baldini M, Colasanti A, Orsatti A, et al. Neuropsychological functions and metabolic aspects in subclinical hypothyroidism: The effects of l-thyroxine. Prog in Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(5):854-859. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.04.009.

- Garber J, Cobin R, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):e1-e45.

- Davies, TF. Pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (chronic autoimmune thyroiditis). UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-of-hashimotos-thyroiditis-chronic-autoimmune-thyroiditis. Published August 2014; accessed July 19, 2015.

- Strieder, TG. Prediction of progression to overt hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism in female relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease using the Thyroid Events Amsterdam (THEA) score. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1657-1663.

- Rotondi, M, de Martinis L, Coperchini F, et al. Serum negative autoimmune thyroiditis displays a milder clinical picture compared with classic Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171(1):31-36.

- Carta MG, Loviselli A, Hardoy MC, et al. The link between thyroid autoimmunity (antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies) with anxiety and mood disorders in the community: a field of interest for public health in the future. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:25. Published 2004 Aug 18. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-25

- Bell L, Hunter AL, Kyriacou A, Mukherjee A, Syed AA. Clinical diagnosis of Graves’ or non-Graves’ hyperthyroidism compared to TSH receptor antibody test. Endocr Connect. 2018;7(4):504-510. doi:10.1530/EC-18-0082

- Barbesino G, Tomer Y. Clinical Utility of TSH Receptor Antibodies. Journ. Clin. Endoc. & Metab. 2013;98(6):2247-2255. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-4309.

- Staii A, Mirocha S, Todorova-Koteva K, Glinberg S, Jaume JC. Hashimoto thyroiditis is more frequent than expected when diagnosed by cytology which uncovers a pre-clinical state. Thyroid Res. 2010;3(1):11. Published 2010 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/1756-6614-3-11

- Helmreich DL, Tylee D. Thyroid hormone regulation by stress and behavioral differences in adult male rats. Horm Behav. 2011;60(3):284-291. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.06.003

- Lee, J and Chung, WY. Subclinical Hypothyroidism; Natural History, Long-Term Clinical Effects and Treatment. In Current Topics in Hypothyroidism with Focus on Development. Ed. Eliška Potluková. 2013.

- Lazarus J, Brown RS, Daumerie C, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Negro R, Vaidya B. 2014 European thyroid association guidelines for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy and in children. Eur Thyroid J. 2014;3(2):76-94. doi:10.1159/000362597

- Korzeniowska K, Jarosz-Chobot P, Szypowska A, et al. L-thyroxine stabilizes autoimmune inflammatory process in euthyroid nongoitrous children with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013;5(4):240-244. doi:10.4274/Jcrpe.1136

- Haugen BR. Drugs that suppress TSH or cause central hypothyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23(6):793-800. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.003

- American Thyroid Association. Clinical Thyroidology for the Public. Clin Biochem. Epub 2018 Jul 20. PMID: 30036510. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.thyroid.org/patient-thyroid-information/ct-for-patients/december-2018/vol-11-issue-12-p-3-4/

Note: Originally published in February 2015, this article has been revised and updated for accuracy and thoroughness.